From Sponsorships to Stress: The Self-Care Industry Is Booming, But Who Is It Really For?

What is “self-care” and who is it for? The answers depend on who you ask.

For civil rights activists like Angela Davis, Ericka Huggens, or Audre Lorde, self care is “not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare”, because self-care sends a message that not only can people survive against the systems of oppression but they can thrive. While, for some corporations, self-care is a billion dollar industry that continues to rapidly grow as one of their best forms of hidden advertising. For some influencers, titling their content as self-care can be the only way it attains algorithmic success, the only way they can secure their sponsorships, the only way they can compete; and the only way they “self-care” becomes their performance of “self-care”.

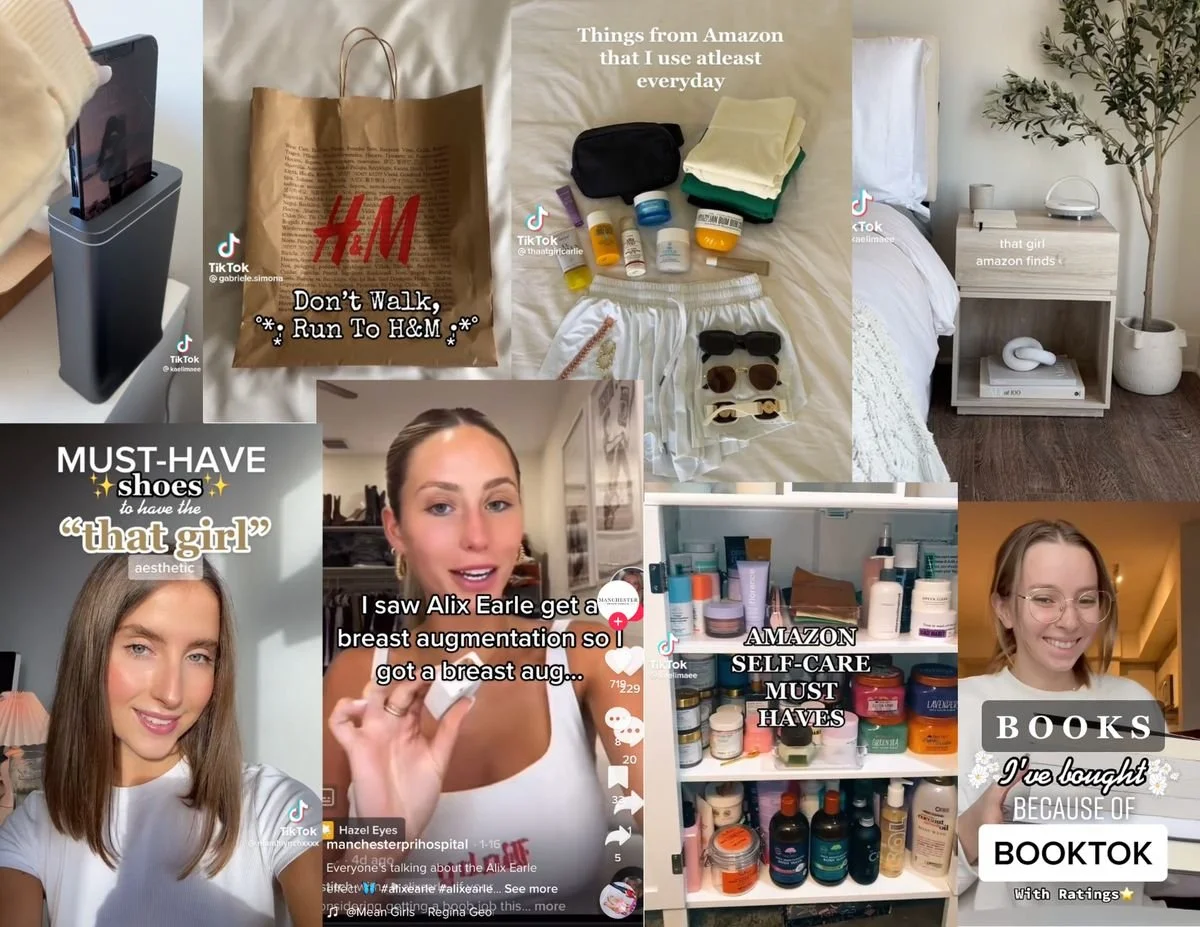

For all genders and ages, self-care can mean a lot of various things, but its commodification and accessibility online can contort its meditative, holistic and anti-capitalist values into a targeted, stress inducing race to compete with both everyone else and your best possible self — and the solution to the stress? Buy the hyperbolically described facial cream, fiber cushion or jaw-enhancing mewing gum so that you have a chance.

Self-care once took back power from systematic oppression but now its industrialization has only fed corporations with more power and influence. Social media has the capacity to continue inflating this commercialization or to deflate it by reminding people that self-care means more than your credit card.

The corporate relationship to wellness is no new issue. For instance, in 1971, L’oreal launched the tagline “Because you’re worth it”, which articulated that if people valued themselves, then they would treat themselves to L’oreal products – that self love could be materialised best through material purchases. This marketing approach hasn’t changed much since the 70s – the only thing that’s changed is the way it's communicated. Billboards or taglines have transitioned into living, breathing influencers that can promote this message in a more natural, parasocial way. It simply feels like a close friend recommending you a product that “changed” their lives. However, because new business, products and influencers will keep flooding the scene, no one process will ever be good enough. Therefore, self-care is implicated as something to always chase rather than a process which can help to healthily sustain your wellbeing. Self-improvement is now often linked to self-care and while both values are healthy and important to life, when they are integrated and used commercially, then businesses reap the most benefits. While the everyday person becomes a struggling consumer, overcome by stress and comparison.

In the fitness industry, younger demographics can feel the need to radically alter their lifestyle in order to feel good about themselves. With trends such as “looksmaxing”, a sense of blame is often integral to their message – if you don’t reach a new physical potential everyday, then you haven’t properly cared for yourself and you could be happier. More and more people are getting pushed to buy supplements or even the most questionable products out there like mewing gum or even worse, the 130 dollar NuFace to try to attain the images set out for them online. Younger generations are getting confused between self-care and self-improvement. “GymBro” content can either demonize self-care as laziness or implicate self-care as only attainable by curating a gym focused routine and purchasing helpful gym products. Similarly, videos that are labelled as self-care feature long compilations of products like face masks, bath bombs or creams. Influencers are supposed to positively influence others but most of the time they end up creating pressure to live up to a certain image instead. The reality is nearly everyone can be made to feel less than and stressed out about self-care because of the rampant product placement in social media content.

However, so many influencers are fighting the battle of commodified self-care, creating content that has no sponsored ties and focuses on mental wellbeing, offering genuine tips and advice. The difficulty arises when an algorithm is in control and when younger generations find it harder to distinguish real self-care from advertising. Self-care is really a stance to take a break from the ever-producing machine of society but its saturation on social media distorts its meaning and harms young people’s perception of themselves. People have to try to remember its initial values and why it was created, and find out what self-care is from within.

Written by Ben Lynch (@Ben_Lynch__)

Edited by Alex Kelleher (@alex_kelleher_)