Gaspar Noé the Provocateur

Argentinian director Gaspar Noé has become an icon in the film world, though not in the most conventional way. For over three decades, Noé has been a provocateur, seeking to revolt and disturb his audience to the point where they might walk out of the cinema. Uncensored violence, sex, jarring strobe lights, nauseating camera movements—anything a film could do to make you turn it off—is the epitome of Gaspar Noé. The problem? He’s an excellent director. From the vibrant colours to the inventive camera work, his films are artistically brilliant. So why the continuous shock factor? Because Noé is obsessed with pushing the possibilities of cinema—without moral boundaries—where no movie can be compared to the next.

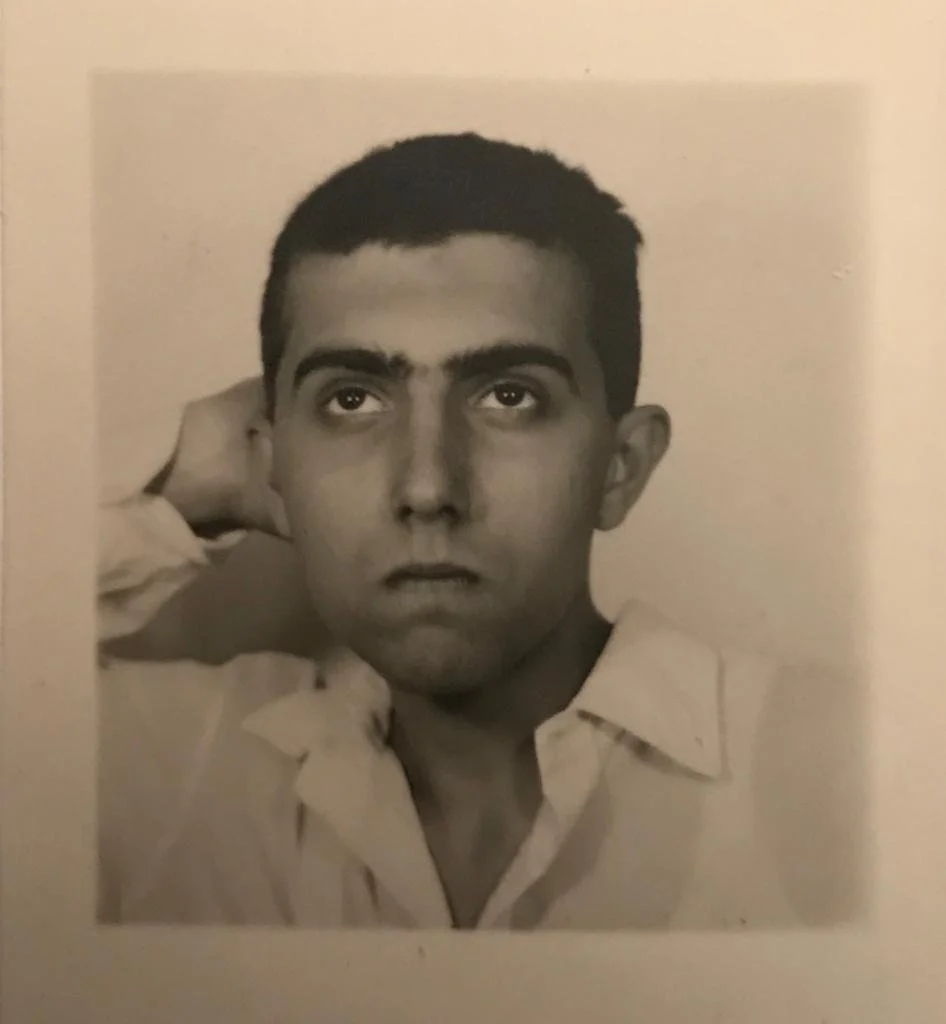

Growing up in Buenos Aires, Noé spent many afternoons at the movies with a childhood friend whose family worked at a local cinema. He became, in his own words, a “movie junkie.” In 1976, his family moved to France to escape Argentina’s brewing military dictatorship. A family friend recommended that Gaspar attend the École Nationale Supérieure Louis-Lumière in Paris, from which he graduated in 1982. His obsession with the grotesque began early: while at university, he even tried to cast his father in a short film as a serial killer. The film was dedicated to his mother.

In 1991, Noé directed Carne, a short film about a horse-meat butcher raising his autistic daughter. The film premiered in the International Critics’ Week at Cannes and found modest success overseas, particularly in Japan. Seven years later, he released his first feature-length film, I Stand Alone (1998), a sequel to Carne. Once again following the butcher, it tracks his attempts to rebuild his life after prison. Narrated in a raw, confessional style, the film is filled with his anger at society, women, immigrants, and his own failures. Reviews varied, but all agreed on one point: the film is deeply disturbing. As Noé himself often says, the point isn’t to over-analyse—just to experience.

That advice applies most of all to Noé’s infamous Irréversible (2002), a sexual abuse story told in reverse. The script was conceived in less than two weeks and shot chronologically in six weeks before being edited backwards. It follows two friends, Marcus and Pierre, as they hunt down the man they believe sexually abused Marcus’s girlfriend, Alex. The film received mixed reviews, but its notoriety comes from two graphic scenes: a brutal murder with a fire extinguisher and a distressing sexual assault scene, filmed in a single, unbroken shot. At its Cannes premiere, the film caused a mass walkout, with reports of hundreds leaving within the first 20 minutes. Some viewers fainted, vomited, or required medical assistance. Interviews with shocked audience members can still be found online.

Despite—or because of—the outrage, Irréversible cemented Noé’s reputation as cinema’s great provocateur. Nearly twenty years later, he released Irreversible: Straight Cut, a chronological version of the story. The effect is strikingly different: characters who seemed like heroes become villains, and the audience can follow events without the disorienting edits and chaotic camera work. Fans still debate which version is better, but most agree that the original best reflects Noé’s signature: violent, disorienting, and unforgettable. As he famously said, he wanted to make a film that felt “like a punch in the stomach,” with violence on screen as disturbing as violence in real life.

Though violence and sex are his trademarks, Noé’s work can also devastate in quieter ways. Vortex (2021) portrays an elderly couple facing dementia and heart disease. Its long, unbroken takes make the film relentlessly uncomfortable, yet profoundly moving. Inspired in part by Noé’s own experience—he suffered a brain haemorrhage in 2021, and both his mother and grandmother died of brain-related illnesses—the film is his most intimate exploration of life’s fragility. Like much of his work, Vortex is a one-time watch: unforgettable, but too painful to revisit.

Gaspar Noé sits comfortably at the bottom of many people’s lists of “favourite directors”—perhaps exactly where he wants to be. Dedicating his career to provocation and boundary-breaking has consequences, but someone had to do it. For cinephiles seeking a director to dissect, Gaspar Noé is more than worthy of study.

Written by Jack Muray(@jack.mrry)

Copy Editor - Niall Carey(@niall.030)